Archives Hub feature for February 2020

Established in 1971, the Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry was a pressure group set up to assist members of the Jewish community in the Soviet Union wishing to leave the country but denied permission. The term “refusnik” was coined to describe these individuals. On hearing the news that thirty five-year-old librarian Raisa Palatnik from Odessa has been arrested for distributing samizdat, banned literature, a small group of women decided to hold a protest outside the Soviet embassy in London. From these modest beginnings grew the campaign on behalf of the refusniks.

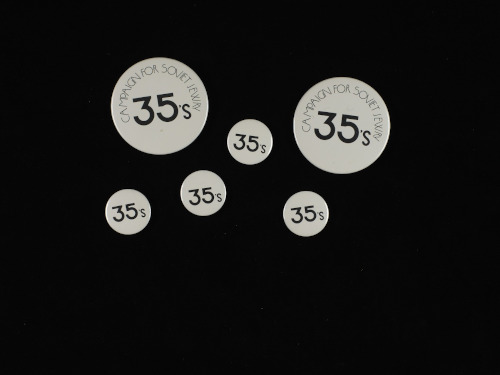

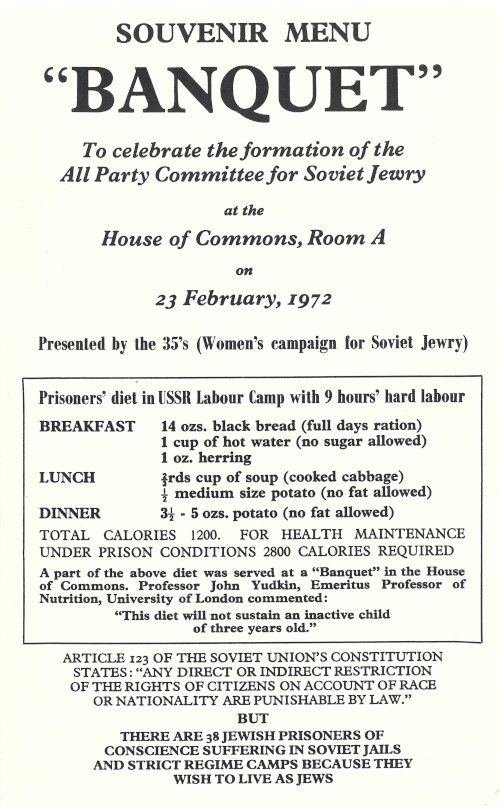

Whilst other groups also campaigned on this issue, the Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry (affectionately known as the 35s due to the average age of the group) was the only one set up and led exclusively by women. Many of the founder members were middle-class, Jewish housewives from North West London who had no previous experience of activism or campaigns. They nevertheless proved themselves to be a formidable force, conducting a tireless campaign to heighten public awareness of their cause.

The group existed in the era before social media and it was a campaign that used the medium of the letter. It organised mass letter writing campaigns to garner support for the cause and also engaged in correspondence with the refusniks whose cases it supported. The archive contains, for instance, an extensive series of correspondence to Members of Parliament from the mid 1970s until the late 1990s, ranging alphabetically from Diane Abbott to George Young, with others such as Betty Boothroyd, Harriet Harman and Margaret Thatcher in between. An equally extensive parallel series of correspondence exists for Members of the House of Lords. The MP Greville Janner was a major supporter of the cause, acting as chairman of the All Party Parliamentary Committee for the Release of Soviet Jewry and later as President of the National Council for Soviet Jewry. The Women’s Campaign archive contains much material relating to his work.

Whilst Raisa Palatnik was the catalyst for the group’s inception — and it was to assist many refusniks over the course of its existence — probably the most well-known individual on whose behalf it campaigned was Natan (Anatoly) Sharansky. At an event in 2018 Sharansky paid tribute to the efforts of both the Women’s Campaign and to Greville Janner in the struggle for Soviet Jewry.

Effective at utilising publicity, the Women’s Campaign produced considerable quantities of material that highlighted the cases of the individual refusniks. There were biographical profiles for each refusnik that publicised and detailed their treatment by the Soviet Union often in graphic detail. Campaigners and supporters also wrote to individuals and their families in the Soviet Union and the archive contains many of the letters sent or received in return. This is supplemented by personal photographs and related material of visits made to the Soviet Union by members of the group to meet with refusniks.

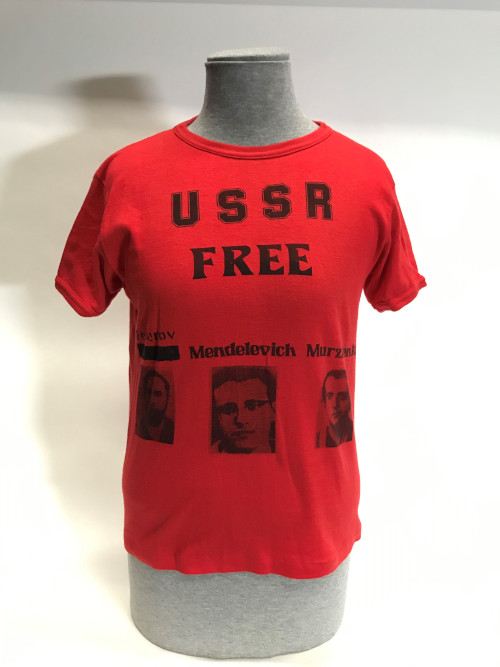

The Women’s Campaign throughout its years of activity was to prove itself to be both highly effective and highly imaginative in its demonstrations and publicity. One such publicity gimmick was sweeping outside the Soviet embassy in London on behalf of the refusniks. As well as organising protests outside venues where Soviet groups — such as visiting athletics teams or ballet companies — were appearing, they became adept at disrupting audiences within the venues. Members secretly wearing campaign t-shirts were strategically placed in the auditorium of a ballet performance, for instance, and would stand as part of a coordinated protest displaying the t-shirts or waving banners. The group have noted that they were viewed as unlikely activists and so were able to circumvent security at venues and smuggle in campaign t-shirts under their clothing.

The demonstrations that the group organised also displayed a dramatic flair: Sylvia Becker, who was one of the founder members, recalls dressing as a ghost when she took part in a protest at Highgate Cemetery in 1974 against a visit by Soviet dignitaries to Karl Marx’s tomb. Costumes such as pyjamas that looked like a gulag uniform and shackles or handcuffs — the latter sometimes used by an activist to chain themselves to railings — were items utilised at various rallies. It is said that after attending one of their demonstrations the Prime Minister Harold Wilson urged them to continue their activities.

The spring exhibition in the Special Collections gallery at Southampton on the subject of protest and protest groups features material of the Women’s Campaign, including t-shirts, a large banner, handcuffs and badges. The exhibition opens on 17 February and will run until May. Further information can be found on the Special Collections website.

Karen Robson

Head of Archives

Hartley Library

University of Southampton

Related

Papers of the Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry, 1970-1993

Browse all University of Southampton Special Collections descriptions available to date on the Archives Hub.

Previous features on University of Southampton Special Collections:

100 years at Highfield: stories from Southampton’s University Archives and Special Collections

The Basque Child Refugee Archive

60 years of faith and conflict

All images copyright University of Southampton Special Collections. Reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.